Adoption through foster care was once deemed unlawful and forbidden by the state of New York, thus forcing children who were in the custody of these families for years to endure the uncertainty of where they will sleep next.

During her career at The New York Times, Edith Evans Asbury was responsible for shedding light on the underreported topic of adoption via foster care in the 1970s. Her coverage of Michael and Mary Liuni’s fight to adopt their foster daughter led to changes in adoption laws, which helped eliminate the stigma of foster parents adopting foster children.

On July 9th, 1962, Mr. and Mrs. Liuni, an Italian-American couple who lived in Tillson, New York, fostered a five-day-old baby girl. Four years later, they were entangled in a lawsuit against New York, pleading with the court for adoption rights over their foster child.

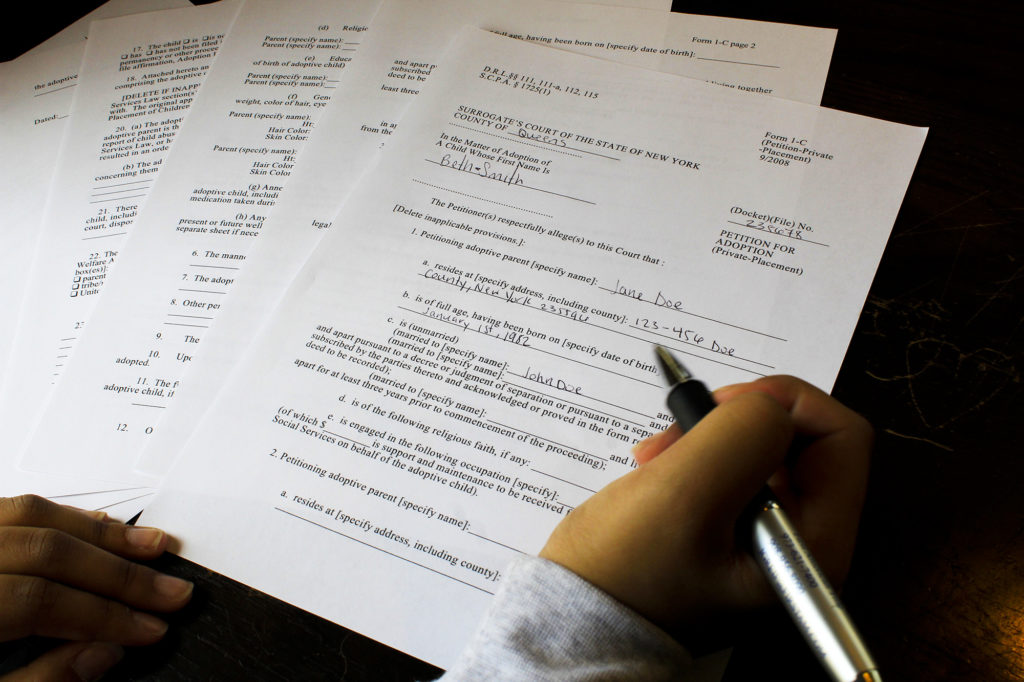

According to court documents, the Liunis’ pursuit of adoption began when they asked about their four-year old, Elizabeth “Beth” Liuni’s availability for adoption and were told, “it was not the policy of the Ulster County Department of Welfare to place children locally for adoption.”

Asbury followed the story as it progressed from 1966 –‘69, providing coverage for The New York Times. In one of her articles written in 1966, she wrote, “their application to adopt her was rejected by the Ulster County Welfare Commissioner because, among other reasons, their ethnic background and coloring differed from hers.”

Had this case taken place in 2019, the circumstances surrounding the Liunis’ adoption case would have been different.

While the current restrictions to adopt a foster child may vary by state, there are no race requirements nor age limitations placed on those who intend to adopt. According to a representative from Adopt US Kids, “In most states, adults of all ages can adopt. There are typically no upper age limits.”

The Liuni case was litigated from 1966 –’69, during a time when birth parents were given priority when it came to a child’s living situation and therefore able to determine whether the child lived with them or continued within the foster care system. In the case of Beth Liuni, both biological mother and father had given their consent for their biological daughter’s adoption when the child was two years old.

During a lengthy conversation with Beth Liuni, now Beth Tomanelli, she revealed that she eventually met her biological mother and learned that her conception was not the result of an affair as was originally reported/as she was first told, but a rape. “She was married at the time and had 6 children,” Tomanelli explained. “I think her husband was abusive too. She didn’t want to bring me up in that household.”

When asked about her biological father, Tomanelli disclosed, “I do know he was Polish.”

Through Asbury’s reporting, the case gained citywide attention. After ten months of fighting for the right to make their family whole, Mr. and Mrs. Liuni were able to attain adoptive rights over their now adoptive daughter. Not only did they obtain legal parental rights, but the case also sparked a conversation concerning the ideology that foster parents should not adopt their foster child.

In an article written in 1969, after the Liunis’ win, Asbury wrote, “two so-called ‘Liuni Bills’ were immediately introduced into the Legislature and were later passed.” The first bill gave foster parents in the same position as the Liunis the right to appeal decisions made by the local welfare commissioners without having to go through the lengthy process of civil litigation. She explains in the same article that the second bill, which “gave foster parents preference in adoption, when they have cared for a child for two years, was vetoed by the Governor in 1967 but was approved by him this year when it was passed again.”

“I’m very grateful for my adoptive parents. My family was wonderful to me,” Tomanelli said.

Through the years of the Liuni Case and throughout the rest of her life, Asbury remained close to the Liuni family, particularly Beth Tomanelli nee Liuni. Asbury attended Liuni’s high school and college graduations and received multiple cards from Tomanelli, n.e Liuni, wherein she expressed her appreciation to Asbury for gifting her a ring.

Tomanelli also explained that Asbury named her in her will and left her a red piano.“I think so, I think I was the closest thing to a daughter that she ever had.”

While Asbury’s coverage publicized the topic of adoption within foster care, foster parents were often still discouraged from adopting their foster children in other states.

Irene Clements, 71, who has resided in Texas all of her life and is an adoptive parent to three children and foster parent to 127 children over the course of 27 years, faced discrimination within the foster care system. In 1974, she and her husband attended a National Foster Parent Association meeting and were asked if they would like to adopt again within the foster care system. “We raised our hands and they told us ‘well, go home,’” she explained.

Clements is now the Executive Director of National Foster Parent Association, a nonprofit organization that was founded in 1972, “as a result of the concerns of several independent groups that felt the country needed a national organization to meet the needs of foster families in the United States,” according to their website, nfpaonline.org.

Due to her inability to bear children, Clements and her husband Billy knew they would follow the path of adoption. “I think adoption was always the plan for us, and we knew that even before we thought about fostering,” she said.

They adopted their first child through an adoption agency in 1971 when the child was an infant. Since then, they’ve adopted a son and another daughter with Downs Syndrome.

She boasts a record of 19 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. “We have a large extended family,” she said and laughed as she heard the shock in my voice. Today, her two daughters are 47 and 32, and her son is 42.

In a smilier instance to the Clements’, Asbury wrote an article titled “Queens Foster Parents Fighting for Return of Child by Hospital” in 1969 which reported the struggle of an older couple, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Marotta, who wanted to adopt their foster daughter. The child was placed in their care since she was five-days old and was taken from them and placed into another foster care family around the age of two. Asbury wrote, “they say the hospital told them they could not adopt Laura because they were too old.” Mr. Marotta was 50-years old, while Mrs. Marotta was 48.

Clements confirmed the pervasiveness of this ideology, saying, “back in the day, they didn’t want you to be over 40. That began to change because everyone wanted to adopt babies.” She continued, sarcastically mimicking what her family told her, “I mean, how old would you be when they graduate?”

Lisa Maria Basile, author of “Light Magic for Dark Times” and editor of Luna Luna Magazine, attests to the inadequacy of resources used to assist foster children. In her article, “Foster Care Youth: We Are Everyone & No One’s Responsibility,” she wrote, “New Jersey’s Division of Family Services provided us with a social worker who treated our situation like a list of grocery items.”

Having grown up in a home with parents who suffered from an addiction to opioids, Basile was put into the foster care system at the age of 12.

In a 2015 story she wrote for Narratively called “My Foster Parents Loved Me. And I Hated Them For It,”Basile detailed the relationship with her foster parents and their relentless attempts to integrate her into their life. She explained, “They were at once my saviors and my captors.”

In an over-the-phone interview with Paul Snellgrove, Director of Home Finding and Placement Services of You Gotta Believe, an adoption agency that seeks to find adoptive parents for older kids and youth, he explained the measures that must be taken if a biological parent chooses to fight for their child in a family court. “For example, if substance abuse is involved, they [parent] have to show they have gone through rehabilitation and is working toward a certain goal within a certain amount of time,” he said.

This measure and those similar to it was put into place in 1997 when former President Bill Clinton signed the Adoption and Safe Families Act. The Act was enforced to prevent foster children from going long periods of time living in multiple foster home and to help achieve permanency for the child.

Ericka Francois, 22, entered foster care at the age of 11 when her teacher reported noticeable bruises on Francois to the authorities. She was placed in the Kinship Guardian Program, a program used to achieve permanency with a relative. In her case, she was placed with her paternal grandmother.

While she did not have to endure living with unfamiliar foster parents, her other siblings did. “Although I didn’t face the harsh realities of being through numerous group homes or residential treatment centers, I watched my younger siblings go through it. I am the oldest of five and took care of my siblings as often as I could,” Francois revealed.

Through similar cases like the Liunis’ fight for the adoption of their foster child, changes to adoption laws have been passed and granted foster parents like the Clements the opportunity to create a family for children in need of one. Through Asbury’s coverage on the topic, the cases gained widespread attention and in return, sparked a change in the flawed system, proving just how significant coverage on an underreported topic can be. However, as seen in the survival stories of Basile and of Francois’s siblings, the relations between the foster care system and the children involved is one that still exhibits needs for improvement.