Is the toilet the best object for human connection? What is the place for puppetry in health? Is sex education all fun and games? Health advocates answer these complex questions.

the best object for human connection? What is the place for puppetry in health? Is sex education all fun and games? Health advocates answer these complex questions.

AHMEDABAD, India–The rain pelts harder and harder on the procession of treading, kneeling, and bowing men and women who wend their way around the green space, guided by a grey stone path. When they reach flooded areas along the path, they barely pause to roll up their pants before pressing their heads towards their knees on the ground. Some stop to touch the bark of trees they come across before beginning the next cycle of steps. They will later say they were compelled to keep moving by the story of two U.S. monks’ 1,000-mile journey by foot and knee.

More than 30 individuals, the majority of whom hail from Pune, are partaking in the Three Steps, One Bow challenge through the main garden at the Environmental Sanitation Institute (ESI), where they are attending one of ESI’s monthly by-donation retreats. ESI, the leading environmental education organization in Gujarat, adapts creative programming on a large scale to promote sanitation and sustainability practices. ESI retreats represent just one of the ways it uses performance art to provide participants with experiential education around land-people connection and sanitation and fertilization techniques.

As a nodal organization, ESI works with 184 organizations for awareness efforts, including coordinating health worker trainings and developing educational materials. ESI teams operate under a family-centered “vibration” system in which they spend at least 3-5 days at villages doing nothing but building relationships before tapping into the collective logic of community members.

“We connect with the people,” said Jayesh Patel, 50, ESI director and son of the organization’s founder, as he rotated a handmade in his hand. “We’re not trying to correct the system as much, or correct injustice or inequality. We’re trying to create a culture where we all take care of each other. When I’m connected to you, things will flow from me to you.”

The philosophy of what Patel refers to as “lab to land” and the “metri” space of connection underlies its nationwide initiatives to promote health and hygiene in villages. Patel likens this inner-to-outer approach to the nature of sanitation: “Sanitation is about internal, not external, cleanliness.” Though the government relies heavily on ESI to pursue environmental health goals delineated in its national health policy, ESI rejects a government-minded focus on results over relationships, according to Patel.

“Software is more important than hardware,” said Patel, referring to the priority of mental reconstruction over the physical construction of toilets. Part of this reconstruction of paradigms is helping people understand how vital proper sanitation is to public health. According to ESI and National Institutes of Health reports, approximately 80 percent of disease in India, 42 percent of illness in schools, and 6.4% of India’s GPD is due to improper hygiene.

As one of the leading advocates for the Clean India national campaign, which stresses proper waste management and hygiene habits, Patel said he believes it “needs to be a people’s program,” he said. “We should be the facilitator, not the administrator, for sustainability and dignity.” Patel relayed one of ESI’s artistic strategies to engage religious communities: it takes advantage of the appeal of spiritual music to gather residents in the rural areas it serves. Staff also tap into multiple modalities of learning, with education efforts ranging from board games, eye-catching booklets and posters, plays performed at schools, and lyrics inserted into traditional garba songs.

The organization also embraces the modern Indian toilet, which his father designed to be more water-efficient than the Western version, as art. Apart from serving as a prime pit stop during his public tours of the ESI grounds, this version of the toilet is incorporated in several projects in development: a toilet garden, cafe, and park.

Patel pointed to the success of the 2017 Bollywood film Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, or Toilet: A Love Story to elucidate the expanding intersection of arts and sanitation education throughout India. The film’s plot revolves around the still-prevalent predicament faced by women in villages lacking toilets: they must rise before the sun and walk a sizeable distance just to discharge their waste naturally. Men, on the other hand, generally use their backyards to defecate.

The Puppet-Masters Master Taboos

It is precisely this situation that freelance health trainer and communications consultant Kirit Shelat, 78, features in his favorite puppet show. Holding a bindi- and red sari-sporting female puppet in his left hand and a turban-clad, silver-mustached man in his right, Shelat relates the story of a couple enjoying their honeymoon at home–until the bride discovers she needs to wake up early the next morning because her husband does not own a toilet. She then threatens to divorce him and bring shame upon his family if he does not construct a toilet in the house, to which her abashed groom concedes, leading to a Bollywood-style happy ending of song-dance.

Shelat has been incorporating puppetry in his health education since working for the government, with a focus on women’s health and family planning, in Maharashtra in 1962. Since retiring in 1997, he has collaborated with countless NGOs and schools to coordinate trainings on sex education and sanitation, two areas close to his heart. Speaking to the status of the nation in its third year of the Clean India initiative, Shelat discussed the limitations of Gandhian sentimentality without acting. “Just to talk about [Gandhi] is not enough,” he said. “We must do something, and Gandhi’s greatest priority was always sanitation.”

“Ultimately, whatever you do, you need to start by spreading information for behavior change” said Shelat. This information exchange is made more entertaining and less top-down with the help of puppets, according to his wife, Surekha Shelat, 74, who creates most of the puppets Shelat uses and is a co-founder of the award-winning organization Ashkar Puppets Kalavrund, which supplies puppets to NGOs conducting education on AIDS. “What we cannot say, the puppets can,” she said, leaning back on her sofa. The use of puppets allows toilet talk and discussion of health topics considered taboo by channeling this dialogue through characters.

Puppets also aid health educators in culturally adapting for communities with religious beliefs and superstitions averse to the ideas of home toilets and contraception. For instance, traditional wisdom still practiced by residents of some Indian villages holds that maintaining a toilet inside the house is disrespectful to the gods. Instead of attacking such beliefs, educators avoid sacrilege by infusing their characters’ teachings with a mix of humor and the gravity of social stigma. The message, albeit comically communicated, is clear: modern toilets are a necessity in order to save one’s status and prevent shame from being brought upon the family.

Apart from puppetry, Shelat develops curriculum for both schools and state-level workshops that trains thespians to perform in villages. It is just as important to fuse the arts and science as it is to incorporate health in formal education, according to Shelat. “The only limitations teachers may face is that they only use their experiences [instead of] keeping the audience in mind.” Shelat works to fill this lacuna with creative projects like a picture book he is set to publish soon.

Playing Games With Your Heart

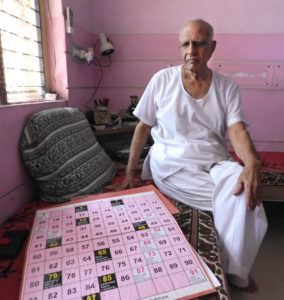

Shelat’s colleague from his time with the state government, Kaushik Desai, 82, takes adolescent sex education to another level of fun and games. Desai, who worked as a State Health Education Officer specializing in family planning, taps into these 32 years of experience to develop board and card games alongside literature on the taboo subject. The games he showcases range from the Operation-type board variety featuring anatomical structures to games featuring cards with questions about sexuality.

Desai explains the incentive for one of his creations, a sexuality-themed version of Snakes and Ladders: as a health officer, he encountered a boy terrified of his own sexuality. The youth was not only ashamed to discuss his nocturnal emissions, but also believed the superstition that 1,000 mg loss of semen equates to 1,000 mg blood loss. Witnessing the extent to which the boy believed his unconscious sexual physiology was linked to premature death sparked Desai to address this fear of sex. “That’s how it started,” said Desai, motioning to his illustrated diagrams that covered the sofa.

“To have less children is against the social structure,” Desai explained. Apart from the pervasive cultural notion that children are God-given, family planning educators must also battle the traditional Muslim belief that removing anything from, or in any way deforming, the body–as with vasectomy–results in exclusion from heaven.

Such cases called for a personal approach to re-educating people that children come from the human body, according to Desai. “Help the child, and you gain their heart,” he said. “That would work as the bridge.” Desai recounts how, as a health officer, he treated a sick child in a village with herbal medicine when his lack of training did not allow him to use modern medicine, thus winning the villagers’ trust with the power of performance outside of his governmental role.

While taboos related to family planning are no longer as common, they have been replaced by superstitions that threaten to stymie malaria prevention efforts, according to Desai. Violence against any beings, including mosquitoes, goes against Gandhi’s teachings on ahimsa.

Desai, who also collaborated with ESI founder Ishwarbhai Patel, and gave a brief illustrated oral history and demonstration of Patel’s modern toilet design before promoting the ESI approach to sanitation education. “We need to appeal to the heart of people,” he said. “Your messages must get to the heart of feeling, touch.” Though Desai said he responds better to logic, he understands that folk dances and other types of performance engage emotion, the lifeline of behavioral changes.

Yet one health clinic official dissents. “Doing performances, songs, and other entertainment and giving out free T-shirts is not how people change,” said Dr. Pankaj R. Shah, Director of the Sanjivana Health & Relief Committee. According to Dr. Shah, behavioral modifications only happen as a result of one-on-one education from practitioner to patient, sans the arts.